The Unused Material

Congratulations on finding the hidden content for our The Art and Making of Control book! The first reader who cracks the code and sends an email to support@future-press.com with this URL in the subject will receive a little present from us!

While working on the book we had the pleasure of spending a few hours interviewing Remedy’s Creative Director, the esteemed Sam Lake. We saved parts of that interview to use as bonus content, which we’ve presented here alongside some wonderful pieces of concept art that also don’t appear in the book.

( Future Press ) Players can tell when a game is weird purely for the sake of being weird. Did you have a methodology for balancing this, or did you feel your way through the process?

( Sam Lake ) Yeah, I would say that I personally go by feel. I’m somehow wired that way—I feel quite secure and at home in that space. The teamwork, which is very much a part of making videogames, was a learning process. It’s a lot of very talented people coming together to create something greater than the sum of its parts. I maybe didn’t understand the need, especially early on, for everybody to be on the same page and get more things written down so that we could properly communicate and understand each other. Even if I knew the answer to a question, I found myself hesitating to say it out loud, so as to not spoil it… which isn’t the best way to communicate ideas to the team. This was something I learned through Control, and I do think we got a lot better at it along the way. It was a constant message from Mikael [Kasurinen, Control’s Game Director] and I to the team: “Let’s be bold enough not to over-explain everything to the player.”

It’s curious how easy it is to fall into the trap of thinking that we are somehow losing something or missing something if our audience doesn’t understand every aspect of what they’re seeing and experiencing. That was something that I was struggling with along the way: having the courage to say, “What do we redact? What do we leave out and not say?” At the same time, it was really important that the lore does make sense, even though we’re creating a story that’s based on dream logic and weird ideas. It should be something that you can piece together, and if you pay attention, there are clues, which, when you combine them, will give you a theory. In entertainment—in works of art, in movies, on TV, in games—it’s easy to break the audience’s immersion if the plot starts to feel like it’s lazily done and doesn’t add up. When that illusion breaks, you lose interest and your respect, and it’s impossible to gain that back.

( FP ) Was the code name P7 originally just a reference to Remedy’s seventh project, or did you always want to tie it into Control’s plot?

( SL ) You can probably tell that we left a lot of things open to interpretation in Control, which we were working on as we were coming out of Quantum Break. In Quantum Break, we were worried that the player wouldn’t understand the complicated arrangement of the timeline, so we decided to add cinematics and dialogue to explain it—all the chronology, how this timeline flows, a cutscene here or there to explain a key point and make sure that everybody understands what’s happening.

When it comes to Control, though, we didn’t want to hold the player’s hand; we wanted the world to do more of the storytelling, and if somebody missed something, that would be fine. That idea came more from Mikael. I think that was a wonderful direction that worked really well. It was very much part of the philosophy for Control: “Let’s not explain it; let’s even intentionally leave it a bit more fragmented so that people can piece it together.” We obviously have our own interpretation of the game’s lore as developers, but there might turn out to be a different interpretation that actually fits and makes sense as well. We should never just come out and say that something is canon, that this is how it’s meant to be understood; everybody decides what they want to take out of it. I love this approach.

Max Payne 2 is another anecdote for this. It has an alternate ending if you play through three times at all difficulty levels, which is a happy ending where Mona Sax survives. To this day, people on social media still approach me and ask whether this ending is canon, whether she’s alive. I might be a horrible person, but I never reply to these questions because it’s not for me to say what the correct ending is—it’s what you decide as a player. And that’s something I feel very strongly about.

At the beginning of Alan Wake, he narrates that “the unanswered mystery is what stays with us the longest, and it’s what we’ll remember in the end.” I believe in that with my whole heart; it’s what draws me to fiction. I’m very much engaged and entertained when there are things I don’t quite understand—I love it. I’m a writer, so I’m always looking for meanings and connections in everything, and I can’t leave these unexplained mysteries alone.

So yes, I’ll spoil it for you: P7 was initially just “Project 7.” Very boring. Then I thought, “Wouldn’t it be nice if it actually meant something?” and out of that came the whole Prime Candidate program idea, and Jesse being the seventh candidate. That’s P7… that’s the story, and now it’s spoiled. It would be so lovely to say, “No, it’s all part of the plan, all of these things were set in stone and thought through years before,” with a bold face, wouldn’t it? Sometimes you can go back and retcon some elements.

( FP ) The work of Carl Jung appears to have had a strong influence on Control’s fiction: what kind of research do you do at the beginning of a project? How much do you dig into this kind of stuff?

( SL ) These things have many beginnings; some of them go back to things I’ve researched that have interested me. I don’t want to come across as too informed on these topics. These days there is also the Wikipedia level of research where you’re thinking idly about something and, instead of going to the library and actually developing theories of your own, you fall down the rabbit hole of Wikipedia links and just keep researching. I definitely process some of that research through the lens of fiction.

( FP ) Did you plan for Jesse’s internal emotional chaos and struggle to be mirrored in the external conflict of the Hiss invading the Oldest House?

( SL ) That is something I was thinking about quite consistently through our games. If you go back to the first Max Payne, he’s a man in turmoil: horrifying things have broken his family and his life. I already thought that he’s the narrator, so we do not even see the real world objectively—we’re getting a version of the world that’s filtered through an unreliable narrator, a hard-boiled cop. Thinking about Max Payne from that perspective, after that initial scene where his family is killed, we don’t see daylight at all—we’re in constant nighttime, and the worst winter storm in the century is battering the city. My thinking is that we take that horrible storm that’s raging inside his head and create it as a tangible, external thing. If I had to choose a simple way of telling a story, that’s something I’d consistently do.

I feel that the inner struggle of a protagonist in an action game is put into their external world and made concrete. Alan Wake might be even more concrete with that: from the deep waters of his mind, he has conjured up this manuscript, and now it’s becoming real. The dark demons of his mind are now the enemies you are fighting against. With Jesse in Control, I wanted the player to form their own theory of what’s going on. Because she immediately feels so at home in this weird world that is facing this horrible threat, you’re bound to question and think about what is real, what isn’t, and how much of this is in her head. Towards the end of the game, when the Hiss does invade her mind, and she’s trapped in that nightmare, I think there is an opportunity for the player to follow this line of thinking: that Jesse is really just an office worker who is imagining these things, and that this sequence is our first glimpse into her actual reality. Our goal is to open these doors slightly and bring in unexpected, thought-provoking possibilities.

( FP ) Discussing the concept of rituals with Mikael Kasurinen, he mentioned that you used Obsessive-compulsive Disorder as a means of contextualizing the world of Control, and that within this world, there are functional purposes and practical reasons for people repeatedly performing the same actions or rituals. Can you talk a bit about that?

( SL ) That is something I had been carrying with me for a long time, and you also see it in Alan Wake with the mystical light switch. That idea goes back to when I was studying screenwriting. I wrote a movie screenplay in Finnish, a horror story, where a light switch was a key element. I had the idea that flicking it made the horrors go away. Certainly, some people suffer from OCD, and it’s a serious matter, but at the same time, a story can draw from it on a fictional and mystical level. Kids often go through a phase of magical thinking as they’re growing up, and in Control, you start seeing the world from that perspective: things have weird connections of cause and effect or are connected by meaning. You are bound to invent rituals in your mind. Religion is full of that, too. It’s a very human thing. That’s what enables people to believe in fiction—it somehow resonates with them and feels right, especially in Control, when you bring this type of OCD thinking into the modern world using mundane stuff around you. We couldn’t quite make certain design elements fit, so we used this kind of magical logic to help those elements make more sense. We explored a lot of different ideas: for example, you need to place coffee cups on a table in the right order or flick a light switch a certain amount of times, which obviously became part of the Oceanview Motel. We had a lot of those ideas on the drawing board, and the overall concept resonated very strongly with me.

( FP ) While your stories have a very serious core, you always find a way to incorporate humor along the way. What was the balance in Control? What was the tone you wanted to set? The Board, for example, is very often genuinely funny.

( SL ) It’s important to me, and we can relate it back to our discussion about New Weird and the challenges of communicating, creating something together. When I first come up with an idea, I have a general sense of the story element or character that I want to create, but I haven’t quite refined it to where it needs to be. I’m still in a place where I need to talk about it with somebody, which always helps me process and refine my ideas. When some of these odd combinations of something disturbing yet funny are forming in my mind, I do get people looking at me like a crazy person. It’s part of the process. I feel comfortable with the idea of mixing these elements and having a strong element of humor in there. It helps make for a deeper, more authentic experience. I sometimes need to go to extra lengths to explain and sell that idea. It’s easier to understand one consistent tone in an experience and focus only on that tone, whereas breaking it is always more challenging. Ultimately, when you succeed in breaking the tone, it makes the writing stronger; however, it takes many iterations to find that balance.

I do think that a humorous element has been consistently present in Remedy games, even when we were dealing with very dark horror stories. Something very exciting that draws me to videogames as a storytelling medium is that we face these different emotions in our everyday world all the time. There is humor present in our life every day. There are tragedies and dark things present, which all kind of meld together and form our lives. Creating these deep video game worlds, it’s not just like in a movie, where you have less than two hours, and you need to be strict about what’s included and what isn’t; a video game can contain a lot of different components coming together over a longer period of time to create a more recognizable, familiar setting.

( FP ) Quantum Break was chock full of interesting optional collectibles for players to discover and read, but their length often felt at odds with the pacing of the action. How did you solve this issue in Control?

( SL ) I very much agree. It’s about finding the proper length for individual elements. I think that the writers on Quantum Break are all really great writers and very talented. Quantum Break has complicated lore, and there were so many ideas we wanted to put into the game, but obviously, it’s a very tight, linear story. A lot of players hate to miss things, and there’s a fear of missing something important. We failed at communicating what’s optional in Quantum Break—sometimes, there was a very relevant thing hidden somewhere.

( FP ) Like Time Stabber…

( SL ) Yeah, which was a great success. That was written by Tyler Smith, who these days is in Hollywood, writing for movies and television. It was a learning process. We had way too much reading for such a tightly controlled experience, and it affected the pacing. If you stop at every computer and spend tons of time reading emails, that becomes the whole experience. This was one of the exciting things about the idea of creating a larger, somewhat more open world where you are not strictly on rails: you are supposed to be exploring and discovering.

It became more about making sure that we are rewarding those who want to explore and find those things. It’s a curious thing psychologically that when you’re forcing information on the player, such as in the form of a cutscene or lengthy dialogue, they might reject it and press the “Skip” button, which of course you need to give to the player these days. And when they do that even once, you have lost them. Then they are gone. The philosophy in Control was to give players fragmented information and too little of it so that suddenly they’re dealing with this unresolved mystery, and they want to learn more.

It’s a really interesting flip that happens, from wanting to skip cutscenes to wanting to find and dig into things. When that happens psychologically, you—the player—are driving the experience; you want more, and you want to find it. Suddenly, all that information becomes much more rewarding.

( FP ) With the Hotline calls, the Darling videos, the FBC dossiers and various other narrative tools being used to reveal important information about Control’s world, how did you keep track of all these different narrative fragments to ensure that the order in which this information is disclosed to the player makes sense?

( SL ) Haha… Excel. I do want to give a lot of credit to our narrative team because I think they did a wonderful job at keeping it together. Going back to Quantum Break, creating this complicated time-travel story, we would discover plot holes quite late in the process that we were shocked we hadn’t noticed before, so then we’d have to go back and fix them. Having that ever-present risk hanging over us in the background was how we learned to be careful with these things. There were some instances where we realized that we already had a document which mentioned one thing and now that we changed this thing, we need to go back to this and fix it. A lot of this very important work was definitely not on me, but on our narrative team.

( FP ) The game is filled with hints indicating that the Bureau’s history goes back a long way, like the numerous portraits of previous Directors that adorn the walls of the Board Room. Are there any details you can share about the Bureau’s background and history?

( SL ) This goes into a lot of conversations I had with the narrative team about certain ideas and elements from early in development: specifically, the forces or societies that have been investigating natural phenomena before the formation of the Bureau, which eventually merged into and became the Bureau. I always felt that we should leave that out of the story, especially for the first game in this world—we shouldn’t focus on that purposefully. This is not urban fantasy, where ancient magic is found in the contemporary world. Instead, our theme is New Weird, so I felt that it was more fitting to focus primarily on the modern, present-day world, with influences dating back maybe decades but not centuries. When you start incorporating dream logic and whimsical, awe-inspiring elements, it becomes so similar to the fantasy genre that it slips unintentionally and becomes fantasy, which I really wanted to avoid. I wanted to stay focused on the contemporary world with the archetypes of these Altered Items—mundane but recognizable everyday objects like a telephone, or a typewriter. We resisted the urge to use too many of the older elements, even though we still occasionally allude to them.

( FP ) Remedy has also explored Norse mythology in many of its previous titles, and it also ties into Control’s lore…

( SL ) Yeah, that’s true. With me and many others at Remedy being Finnish, for the first time we proudly delve into the Finnish mythology as well. Sure, we are a Nordic country, so Viking stuff is close to home, but I just felt like it’s time to put the Finn factor in.

( FP ) Ahti is obviously the embodiment of that “Finn factor” and it’s clear that you had a lot of fun coming up with the way he speaks. Do you have a particular favorite among some of his many strange idioms?

( SL ) There are lots. One that I really like is when Ahti says, “You are not yesterday’s grouse’s son,” which in Finnish is “Et ole eilisen teereen poika,” which just means that you are in the know and not dumb. It’s an interesting journey finding the etymology of certain sayings—there are surprising things to learn. Finland was under Swedish rule for a long time, and we still have a Swedish-speaking minority; everybody needs to learn Swedish in school, so we have a lot of things in our language that come from Swedish. When Swedes make a toast, they raise their glasses and say, “Skål,” which means “skull.” This actually comes from Viking times, when they would knock the skulls of their enemies together as a victory toast. These days, nobody thinks twice about it—about how it’s a really horrifying thing to say, “Skull!” You discover a lot of these weird, curious historical things when you dig into it. Idioms fascinate me, and it was interesting to look into the Finnish ones.

( FP ) We found it interesting that you gave Ahti an old portable cassette player. Product placement has been a thing in previous Remedy titles, so this seemed like the perfect opportunity to give a nod to the official Sony Walkman, but you didn’t go in that direction. Was there a lore-based reason for choosing to avoid showing real-world brands inside the Oldest House?

( SL ) Not really… it just didn’t end up being a focus in Control. Certainly, we had interesting exercises and adventures into product placement with Alan Wake, where we made an effort from the business side to go into that. It’s a hit-or-miss thing, though. With the idea that these games are set in the present-day world, I would love to use real brands, but many of those brands make absolutely no sense to chase and acquire because we would gain nothing useful by doing so. It’s a tricky thing, all in all. It’s become more difficult; if you go back to the first Max Payne, nobody cared—you could talk freely about real brands, and there are a lot of them in there: the Beretta pistol, Mercedes-Benz, etc. We were working with Rockstar Games and I might be remembering it wrong, but I think they may have gotten sued for something in Grand Theft Auto. I remember when we went back to make Max Payne 2, everybody was really paranoid and careful about everything—all the brands had to be taken out. In Alan Wake, we had the business drive to try to have product placement. I think the Energizer battery one made a lot of sense, but the Verizon and Nissan ones not so much. Product placement wasn’t a focus in Control; we were focusing on other things.

Lore-wise, I think the lack of branding makes sense for the Bureau. They’re paranoid and careful about not bringing in the contamination associated with certain brands into the Oldest House. I wanted these iconic objects from recent history, like the classic telephone and the portable cassette player, which felt like the perfect fit. We ended up working with Sony on the reveal at E3, so under different circumstances there might have been a chance to do a product placement, but we were already really far into development at that point, so we just never talked about it.

( FP ) One final Ahti-related question: Coming up with the lyrics for the Sankarin Tango must have been pretty fun. Did you write the song in English?

( SL ) No, we wrote it in Finnish. The curious things about Finns and Finland is that we have a really strong, vibrant tango culture, and an annual competition to crown a male and a female singer as “the king and queen of the tango.” That was a thing when I was growing up, and it still is today. There’s a famous Finnish author and filmmaker, Aki Kaurismäki, who was interviewed for a well-known tango documentary in Finland, and during the interview he spins this yarn claiming that the tango actually originates from Finland, and Finnish sailors took it to Latin America. He goes on and on about that, so of course Ahti had to be a tango-lover, and I felt that he deserved a tango of his own. Given that Martti Suosalo is also a great singer and has done musicals, I thought it would be perfect if we could get him to sing it, so I was looking at this idea with Petri Alanko [composer on Control]. I haven’t really written song lyrics before; we’ve done some collaborations with Poets of the Fall, but how that worked was that I had an existing poem or a story, and someone else took that and created lyrics out of it. This was the first time that I actually wrote the lyrics, and I wrote them in Finnish. The idea was to establish a Remedy Connected Universe which will be all about the continuum of Remedy game lore, in a way. Writing the tango in Finnish makes it part of the lore—something you can discover. I’m ridiculously proud of that achievement, and so happy. When Martti sang it in the studio, Petri Alanko—who composed the melody and is very much an artist with a big heart—had tears in his eyes when Martti was performing it, he was so taken by it.

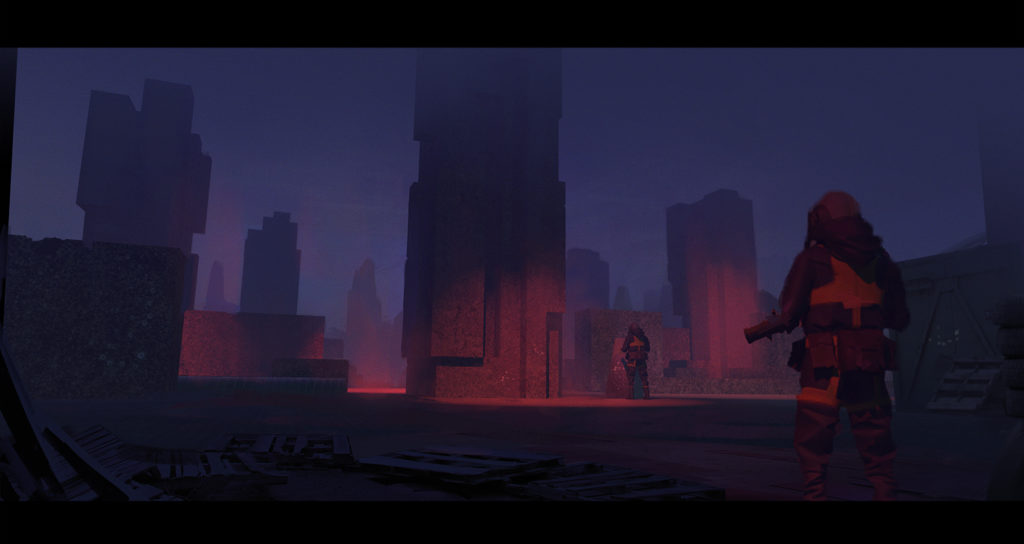

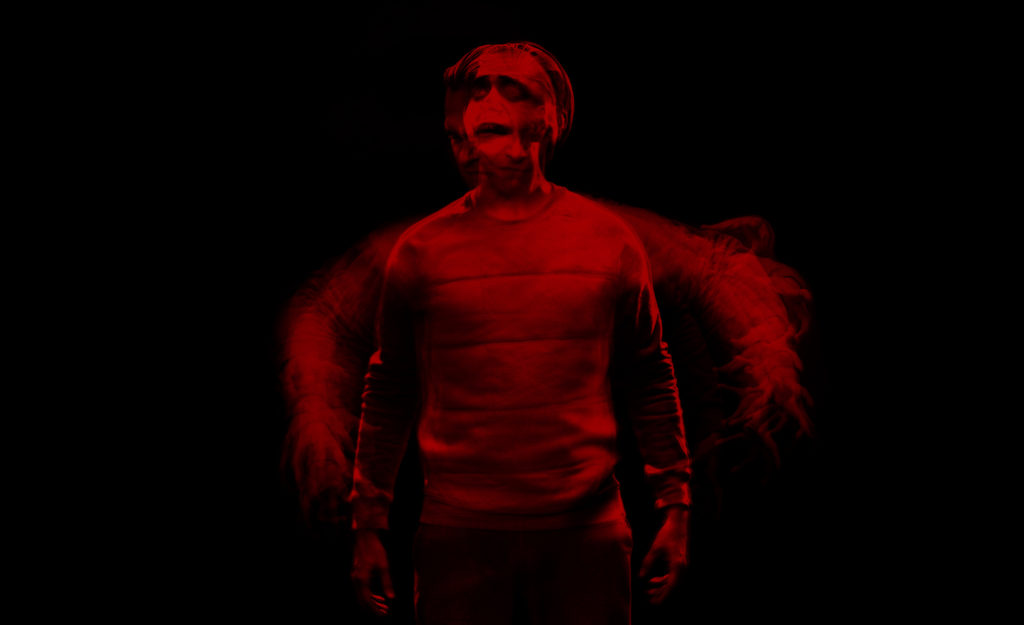

( FP ) Switching gears, this early concept shot of Dylan is very cool. What can you tell us about it?

( SL ) This comes from a test shoot with our cinematographer, Mikko Riikonen, who was very much part of the stylization. Jumping to our cutscenes, which we have very few of compared to earlier games, this was an interesting challenge to keep the amount of material very low. We needed to go with a very stylized experience for our cinematics, which led us to the idea that our cutscenes are almost hallucinations—visions cut out of time and space, of which we see only glimpses. As a reference, I talked about Stanley Kubrick’s fascination with single-point perspectives and being ritualistic, very symbolic and centered—that was a big inspiration for our cinematic style. I wanted to have recurring visions: for example, Trench behind his desk, then Jesse is behind the desk in the exact same pose, then Dylan. Who is in control and who is the real Director? The Service Weapon—the Director’s gun—held to the head, and Dylan mimicking that with his fingers… these recurring images, plus the idea of using blended videos on top of that, came from our early experimentation with very disturbing live-action elements, combining elements and merging them, which also sort of represents the way the Hiss works.

( FP ) There always seems to be an added layer of meaning attached to the names in Remedy titles. How much thought goes into finding the right name for each character and location in your games?

( SL ) Some of them come easy; others take a longer time. Obviously naming the game, going back to Max Payne, is a complicated process which takes time and multiple iterations—especially when you try to use the character’s name as the name of the game, it needs to work as both. With Quantum Break, we had already made the shift, and planned for that game to have more of an all-star cast. Actually, I feel like that decision was made early on, but due to the various obstacles and challenges throughout development, it ended up being a bit more of a Jack Joyce game than we were thinking initially. With Control, the idea was definitely not to name the game after the main character. It was very clear that it wouldn’t be called Jesse Faden; rather, it would be the name of the world, and the term “Federal Bureau of Control” comes from that.

Early on, we were considering calling it the “Bureau of Altered World Events,” so the game’s title would have been AWE, but that was very early on, and we ultimately went a different direction. The idea that resonated with both Mikael and myself was “Control,” because it goes into not only the story, but also the gameplay: you are controlling the environment with your powers. It felt perfect, and to be honest, we were expecting that we wouldn’t be able to get a trademark for that name, which is a complicated process. We were positively surprised that we could name the game Control. As a reaction to that, “Federal Bureau of Control” became the name of the Bureau because they are a clandestine organization, so the name needs to feel like it could be a name of a government agency. At the same time, the name doesn’t tell you anything because the Bureau operates in secret. In keeping with this ritualistic theme, names matter—they carry a lot of significance and power. So, it’s important to me to think about the names.

( FP ) We couldn’t interview Sam Lake without asking: What’s the story behind the “665: Neighbor of the Beast” recurring gag in all of your games? It’s been around ever since Max Payne…

( SL ) You can’t imagine the amount of groans that I get from the rest of the team when I keep sneaking it in somewhere. People roll their eyes and say it’s not funny anymore, we’ve done that. I keep trying to slip it in. I did at some point come up with this idea and was entertained by it. I also found that somebody else had the same idea separately, earlier than I did, which goes to show that anything you think you’ve come up with for the first time has already been done in some way. As for me, though, I got the idea out of nowhere while working on Max Payne and found it funny and entertaining.

( FP ) In 2013 when you announced Quantum Break, you also talked about Alan Wake 2 and showed a sealed crate full of Alan Wake material stashed away in the Remedy vault, waiting to be unsealed when the time is right. Do you feel like this crate is any closer to being opened?

( SL ) Nothing to add to what’s already been said. I will keep my fingers crossed and keep bringing it up. To be honest, all of this is close to my heart… I can’t help but come up with ideas related to Alan Wake 2 and that crate. They’re active in my mind, coming and going. So far, the complicated thing is to make them happen, but as of right now, I have no news.